When to wade in

I live in a bubble. I think all social media users do to some extent. The accounts we follow, the stories we engage with, the photos we like and the ads we click on all begin to curate our own personal echo chamber.

Amongst the dog rescue videos, Taylor Swift clips and ads for a capybara lamp that I will eventually cave and buy, my echo chamber is politically engaged, socially progressive, environmentally conscious and inclusive. There are exceptions of course. Everyone has that racist uncle, an ex-colleague that thinks covid is a hoax or an old friend that refuses to use preferred pronouns.

But for the most part, I find myself in sync with the majority of my online cohort. There is a small portion of my online world comprised of what I would describe as activists. These people are to me a kind of weather vane for important topics and progressive values. It is rare that my opinion deviates from theirs, and on the odd occasion that it does, I deeply question my own position.

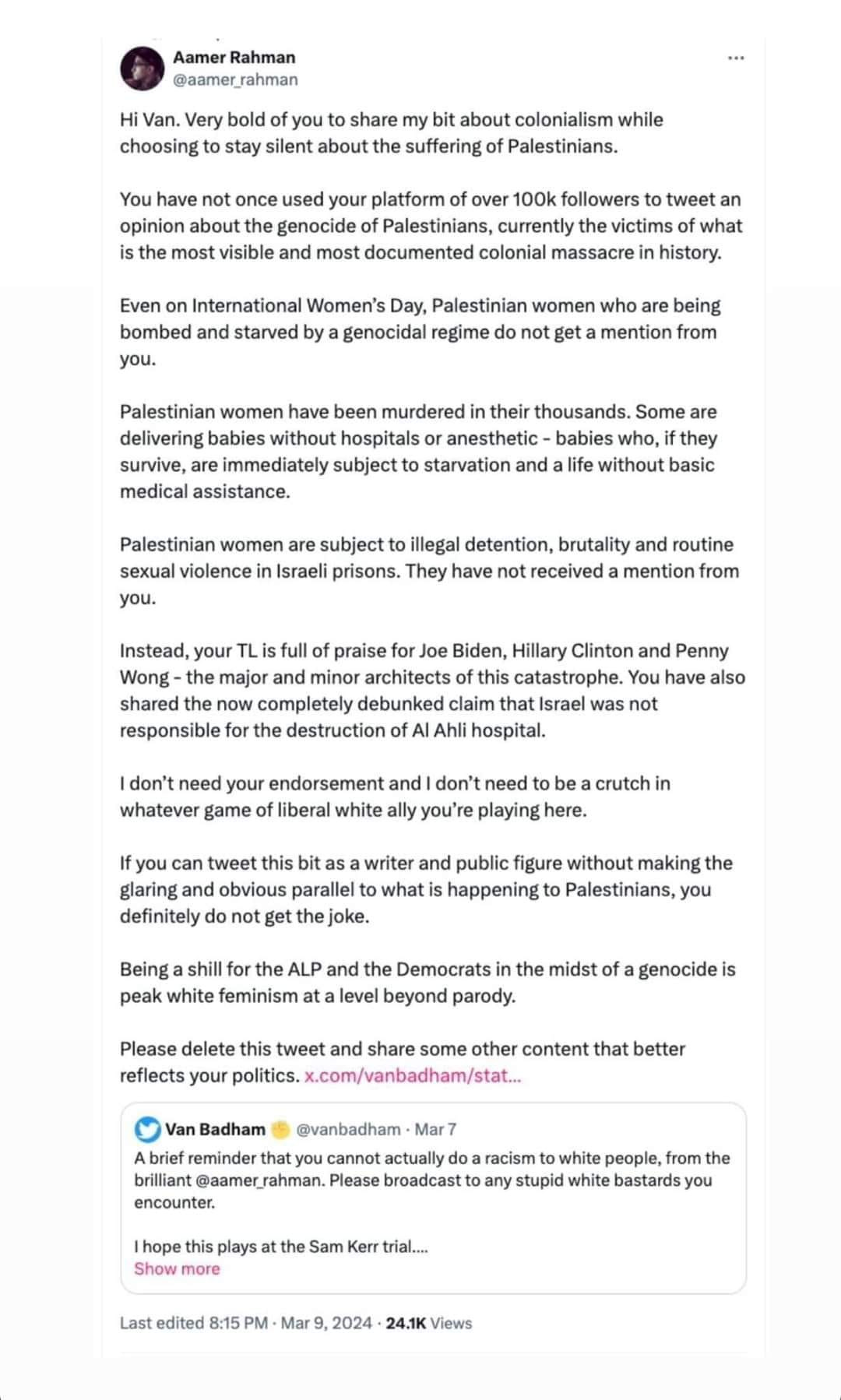

Such an occurrence presented itself this week. Several friends weighed in on Aamer Rahman’s response to Van Badham’s reposting of his thoughts on colonialism and reverse racism. If you didn’t see the exchange, here it is:

In the eyes of Rahman, Badham and others in her position have a responsibility to weigh in on the genocide in Gaza. This is not a revolutionary idea, of course there’s an expectation that journalists and social commentators will use their platform and privilege to draw attention to the important issues of the day and lend their voices to the disenfranchised. Most seemed to agree that Rahman’s criticism of Badham was justified, and I can’t say I entirely disagree.

So where did my opinion differ from that of my friends? Well, the inference appears to be that staying silent on this issue precludes Badham from identifying as a feminist or a progressive. But if this is the case, where do we draw that line? Couldn’t this send us down a rabbit hole where we expect every journalist, regardless of their area of expertise, to comment on every cause? It’s not feasible, in my opinion, to expect that.

For example, as far as I’m aware, neither Rahman or Badham have spent much time covering the crisis in Sudan. Recent reports estimate that up to 10 million have been displaced by the conflict, 25 million are currently experiencing food insecurity and approximately 15,000 have been killed since fighting broke out last year. Are we rescinding the memberships to feminism and progressive politics to every journalist and social commentator that has failed to adequately address this comparable humanitarian crisis? If we did, the ranks would be dwindling.

It is a sad fact of reality that not all news stories will be given equal consideration. Just as missing black women should gain the same attention that Gabby Petito’s disappearance did, and indigenous deaths in custody should illicit the same outrage as Aleksei Navalny’s demise, our eyes (and aid) should be as firmly planted on Sudan as it is on Gaza and Ukraine. But I don’t see anyone drawing the same parallels here.

It is not just those with a public profile holding each other accountable over this issue. An acquaintance of mine felt silence on this issue was a friendship ending offense. And yet, silence there has been. In contrast to say the Voice Referendum, where two opposing sides battled for months in the public arena, calls for a ceasefire, increased aid and more coverage of the atrocities playing out in Gaza have been largely met with silence. At least within my own echo chamber.

(I should note that I speak here of the Australian experience, I realise that in places like America, support for Israel and it’s actions are comparably high).

So why silence? Why are fewer people changing their Facebook pictures to the Palestinian flag, when they were proud to display yellow and blue? Why did war turn Zelensky into a beloved celebrity, but the names of the Presidents of the Palestinian State or its leaders remain largely unknown? Why are people quick to show staunch public support of Ukraine, but tentative to pass comment on Gaza?

Well, I don’t have all the answers, but I think it’s a combination of a multitude of factors. The war in Ukraine and the genocide in Gaza are vastly different conflicts. One is a territory grab, the other an ideologically fuelled extermination, but that alone doesn’t explain the vastly different public responses. After all, shouldn’t genocide illicit a stronger response?

Let’s start with how clearly the antagonist can be identified in each example. The Cold War, the very hot conflicts it was comprised of, as well as decades worth of Hollywood movies and a tyrannical strongman at its helm, have firmly established Russia as a historical foe of the West. On the other hand, due to our strong alliance with the United States, and theirs with Israel, the lines are blurred. Israel is essentially the political equivalent of a friend of a friend.

There’s also the fact that Ukraine was a passive participant in the conflict with Russia, and was in no way complicit in the escalation of that conflict to active warfare. In the case of Israel and Palestine, this is where things get exponentially murkier.

It can be argued that Hamas and its allies, when launching coordinated attacks in October of 2023, including on civilian targets and taking civilian hostages, did not represent the wishes of the Palestinian people nor have the support of their leaders. Regardless, it predictably propelled Palestine and Israel into open warfare. To many, especially those unfamiliar with the underreported state of Apartheid inflicted by Israel, this appeared an entirely unprovoked and therefore unjustifiable attack.

I want to make it abundantly clear that just as there is no conceivable justification for genocide, there is equally no justification for attacks explicitly targeting civilians. I mention the shocking October attacks to stress how uncomfortable it is to defend and support one actor when atrocities were committed by both sides. We’re human, we feel most comfortable with an uncompromised ‘good guy’ and an irredeemable ‘bad guy’.

Then consider that most of us have a healthy trepidation for weighing in on politically hot topics we don’t confidently understand. For those largely unfamiliar with the origins of either conflict, lets face it, it’s far quicker and easier to get a grasp on the 10-year-old war between Ukraine and Russia, with the escalation of that war to invasion only two years old, than it is a complex 75-year-old conflict that has escalated to violence innumerable times.

Aside from the comparisons between Ukraine and Gaza, there are other reasons that people may not be speaking out. For one, many have trouble reconciling that the victims of one genocide have become the perpetrators in another. Jewish history is saturated with violence and discrimination, they have suffered as a people in ways its hard to comprehend. You don’t have to be a history buff to easily conjure the inescapable images of skeletal Jews in concentration camps, so there will inevitably be a hesitancy with reframing the descendants of Auschwitz survivors as the instigators of a new genocide. No one wants to be labelled anti-Semitic and there is an understandable concern that openly supporting Palestine will be seen as exactly that.

In what might seem a rather trivial further argument, I do not think the effect of celebrity support for Israel should be underestimated. For better or worse, celebrity culture exerts considerable influence. Whether it’s earned or not, we place a degree of trust in certain celebrities and hold them to a high moral standard. When treasured icons are steadfast in their support of Israel, it again gives one pause. As does the apparent backlash for speaking out in support of Palestine. Models Gigi and Bella Hadid have lost modelling contracts as a result of their participation in protests, actress Melissa Barrera was fired from her role in Scream VII and Susan Sarandon was fired from her talent agency. If these kinds of repercussions are to be faced by the rich, successful and wealthy, isn’t it reasonable to assume that journalists and ordinary Australians may both be considering the backlash they may face in speaking up?

I strongly believe there is no pride in ignorance, and I equally believe we all have a responsibility to be politically engaged. None of what I’ve said negates that. I just ask that before we strongly condemn someone’s silence, no matter how conspicuous that may seem, we consider some of what I’ve written above. There is nuance in the reasons someone may stay silent. For an independent journalist it could be fear of losing the next commission piece that will pay their rent. Maybe your silent friend simply doesn’t have the resilience to cope with a barrage of criticism? Social media is a magnifying glass, but we simply can’t give all our energy to every cause. In a social media landscape that currently seems saturated by world conflicts, some may simply see their own value in bringing awareness to less visible causes. That doesn’t mean they don’t care about the ones they aren’t addressing.

At the end of the day, the message here is just to be kind to each other. There’s enough hate and judgement on the internet. I recognise my own trepidation in stepping into a more controversial space in which I am admittedly no expert. I’m not confident I’ve made a clear point or concise argument, so if you’ve read this far, I thank you.